L’atelier Muse – The Knitted Life of Marie Rose Lourtet

She knits houses from string, and miniature masks; magnificent maps and impossible-to-wear dresses. Just twenty-five miles north west of Paris, not far from the legendary house and famous water lilies of French Impressionist, Claude Monet, Marie Rose Lourtet simply and seamlessly knits her life.

From the moment you step beneath the red-tiled roof of the home she shares with husband, Jacques, you know you’re among artists. The couple of have been working from the same space, creating art, and blending it with family life, for over thirty years. Mary Rose and her husband both, of course, possess that elusive, and unaffected sense of style that the French seem to have been born with. They are casually dressed, in a chic-without-even-trying manner, and this same unstudied air is also present in their home.

Intricate pieces of the couple’s art can be found, both upstairs and down, on nearly every available surface in the home, and it’s clear that their individual visions do inform one another’s art. Though Jacques sculpts in wood, and Marie Rose in wool, their work compliments each other, even as it contrasts. Paintings, sculpture, collage and textiles create a feast for the eyes; yet somehow never compete with each other for attention. Even the stuff of their everyday lives – family photos, keepsakes, grocery lists, and telephone doodles – seem artfully arranged, no doubt by accident and not design. For people like Jacques, and Marie Rose, who both speak a visual language, art is everywhere, and life is art. It would be impossible for them not to arrange the fabric of their lives in a way that is pleasing to the eye.

Perhaps the most ingenious and impressive display of all, Marie Rose’s work in progress, is pinned to an enormous corkboard that takes up an entire wall of the couple’s living room. On one side, long metal pins anchor about dozen tiny white knitted faces, punctuated with electric blue eyes, or bright red noses, or yellow lips. Some are clearly unfinished, their live stitches held by stitch holders, or bits of brightly colored string. The long pins hold the little lacy masks away from the board and allow them to move gently in the slightest breeze. At times they seem to be in conversation with one another. Part of a planned series entitled 365 Heads, about half that number were exhibited in London’s Craft Council Gallery in 2004.

Perhaps the most ingenious and impressive display of all, Marie Rose’s work in progress, is pinned to an enormous corkboard that takes up an entire wall of the couple’s living room. On one side, long metal pins anchor about dozen tiny white knitted faces, punctuated with electric blue eyes, or bright red noses, or yellow lips. Some are clearly unfinished, their live stitches held by stitch holders, or bits of brightly colored string. The long pins hold the little lacy masks away from the board and allow them to move gently in the slightest breeze. At times they seem to be in conversation with one another. Part of a planned series entitled 365 Heads, about half that number were exhibited in London’s Craft Council Gallery in 2004.

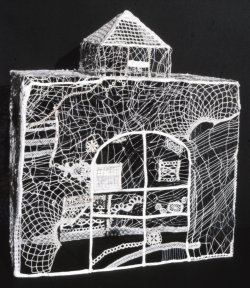

Above the masks, pinned to the very center of the corkboard wall, is a large, very colourful and quite intricate piece of knitting. Measuring about four feet across, it is roughly the size of a small dining room table. At first glance it resembles nothing so much as a three-dimensional knitted map. Like the view of a distant land one might see from great height, with field boundaries, woods and coastal outlines clearly delineated. At closer inspection, mountains give up their shaping secrets as increases and decreases in the knitted fabric become visible, while coastlines map the profiles of mysterious faces, like masks massed together. In one side of the knitting there are three circular needles, placed end-to-end, holding hundreds of live stitches in place. Always present, and within reach, never hidden away in a knitting bag, this work in progress is the perfect metaphor for the way that knitting and the artist’s life meld and compliment each other.

Born in Strasbourg in 1945, Marie Rose attended school only sporadically. While she doesn’t remember learning to knit, she began making things from wool and other found objects when she was just a little girl. From a very young age, she says, she has been “a storyteller; a maker of visual stories,” – sometimes real, and sometimes imagined. She began knitting these stories in her teens, she thinks, or possibly her early twenties. Her first knitted tales were flat, though eventually the knitting began to take on some relief.

In the late nineteen sixties Mary Rose’s work came to the attention of the prominent French artist Jean Dubuffet, considered by many to be the “father” of the Outsider Art movement. Dubuffet coined the term Art Brut, or Raw Art to describe the creative work of individuals who are self-taught, or those who, for a variety of reasons, were “fortunately impervious” to being taught how to make art. This group included the naive, the innocent, the self-taught, the visionary, the intuitive, and the eccentric. (It also included, controversially, the schizophrenic, the developmentally disabled, the psychotic, and the obsessive compulsive.) Mary Rose’s work was championed and celebrated by this influential artist, with whom she shared a lengthy correspondence, and she has been associated with Outsider Art ever since.

Despite wide acclaim as an Outsider Artist, she still feels she has to hide the nature of her work-in-progress “behind a book” when she’s away from home. Pinstriped French businessmen are simply unused to seeing women on trains knit anything other than “layette”, or baby clothes. While travelling to and from Paris, in preparation for the 2004 Crafts Council Gallery exhibition, she felt that people seemed surprised and judgmental about the types of things was knitting, so she learned to be discrete about it. Jacques theorizes that French people still hold to outmoded stereotypes, based upon what a woman of Mary Rose’s age should be knitting – namely traditional, “grandmotherly” things. Mary Rose, who knits things “uncontrollable and wild,” challenges these notions. This, says Jacques, is what people find shocking, rather than the knitting itself.

“It’s like breathing,” she says. “I have always felt the need to recount things. I go everywhere with my little notebooks, pieces of material and wool. It accompanies me, it’s the story of my life, sometimes very complicated, very dense, and sometimes much clearer …knitting allows the thought and the imagination the time to travel, to create images.”

© 2006 Brenda Dayne. Images courtesy of the artist. All rights reserved.

Originally published in Interweave Knits Magazine, Fall 2006.

Afterword: Shortly after this article was written, in the autumn of 2005, I received word from Marie Rose that Jacques had passed away. I was saddened to hear of his death, and will always remember the pride with which he spoke of his wife’s work, and the love in his eyes when she spoke. Tonia and I feel lucky to have spent an afternoon in the company of two such extraordinary artists. Neither Marie Rose nor Jacques spoke English and, as Tonia and I don’t speak French, we are forever grateful to Kate Gilbert, and her charming husband. Without their company and translation services that afternoon, the experience would not have been possible.

I believe it was Mary Rose, was it not, whose beautiful white lace wedding gown-like work was a tribute to her mother’s disintegration into Alzheimers – a very moving work and very beautiful. Trying to remember where I saw this – Knitting in America???? Not sure, but I am now on a mission to find out!

I believe you’re thinking of Katharine Cobey:

http://katharinecobey.com/portrait.html

She was indeed featured in the book Knitting in America.